Adventures with Walter

Walter Pitman and I met by chance in the spring of 1962 when I visited the Lamont Geological Observatory as a prospective graduate student. After a tour of the campus he led me to Professor Jack Nafe in the Oceanography Building for an interview. Nafe was perplexed as to why I was so late in applying. Columbia’s Department of Geology was already accepting the students that were to arrive in the fall. Aware of this snafu, Walter informed Nafe, who was his own academic advisor, of my 5 months experience at sea on the Woods Hole research vessel Chain, not quite comparable to Walter’s own 9 months on the Vema. Walter elaborated that I had also majored in physics with proficiency in acoustics, comparable to his own experience that had gotten him accepted. Listening but still perplexed, Professor Nafe instructed me to derive Maxwell’s partial differential equations on his office blackboard. No sooner than I had filled the blackboard with the necessary scribbles and laid down the chalk, Nafe announced, “Show up in September, but you will need to maintain the same A-level grades to continue as was required of Walter.”

Clearly, without Walter’s intervention, my desire to become an oceanographer would probably have evaporated that very day. Our friendship blossomed through graduate school and grew even stronger beyond. We eventually co-taught Plate Tectonics for many years. Yet, we never had the opportunity to go to sea together.

Then one day in March, 1993, a telex arrived from Moscow with an invitation to participate on a Russian oceanographic expedition in the Black Sea to access the environmental impact of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor explosion. Walter and I were already intrigued by the Black Sea’s recent rapid transformation from an ice age freshwater lake to a saltwater sea. This curiosity had been hatched during conversations with John Dewey as we were working together on a Plate Tectonic synthesis to explain the evolution of the Alpine Mountain chains. The Black Sea had been a stumbling block. Was it an ancient remnant of the Tethys Ocean, or a younger rifted basin more or less contemporaneous in age with the opening of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans? Without much hard evidence, we punted for the latter explanation, which turned out to be mostly true; the opening commenced in the early Cretaceous above a slab of the subducting Tethys.

The unexpected request from Russia was an opportune chance to explore a much younger history of the Black Sea. Although first hesitant, Walter eventually became too curious to be left out of the venture and bought his plane ticket with less than a week to spare. We and our summer intern, Candace Major, set off to Moscow, where we spent our first evening at the home of Misha Kogan, later to join Lamont as an invited scholar. Walter, Candace and I departed the following morning in flight to Anapa near the Kerch Strait that separates the Black Sea from the Sea of Azov. Upon arrival, we set out in a converted WWW II ambulance along a winding road for a four-hour trip to the seaside laboratory of the Southern Branch of the Shirshov Institute of Oceanology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, located at the edge of a forest of evergreen trees at the foot of the Caucasus Mountains. Their freshly painted Research Vessel Аkvanavt would be our home for the next two weeks.

Our sonar, nicknamed CHIRP. arrived a few days late with apologies from the truck driver who pointed to bullet holes in his door delivered by unsuccessful road-side bandits.

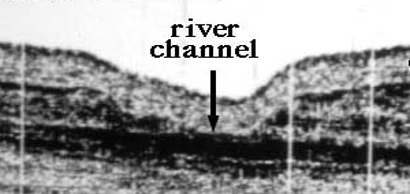

As soon as our equipment was loaded aboard our Research Vessel Аkvanavt we departed to the region where the Kerch Strait enters into the Black Sea. Our literature search had revealed a deep incision (now buried) beneath the floor of the Strait, presumably cut by the ancient Don River during a lowstand of the Black Sea’s surface during the last Ice-Age, and leaving the Sea of Azov dry. Walter was on watch in the tiny shipboard lab below deck, when the CHIRP recorder displayed a continuation of the same river. Here it was some 50 miles from shore and on the outer edge of the Black Sea continental shelf in water that was more than 80 meters (>250 feet) deep. Walter immediately recognized the cross-section of a meander with its inner point bar, now buried beneath 2 meters (~6 feet) of younger sediment.

I was awakened from sleep in the upper bunk of our two-person cabin to see the evidence. Our chief scientist, Kazimierus Shimkus, was in an animated discussion with Walter. How were they to explain the cover of the younger sediment that was equally-thick outside the channel as it was inside? If the channel was a terrestrial river bed as Walter had surmised, then the riverbed should have been filled with material delivered by the pounding surf of a rising sea surface. But the cover had the same thickness everywhere. It was not concentrated in the channel.

Taking advantage of this unexpected discovery, Kazimierus took a brave risk. He delayed our transit to the margin of Ukraine that had been the prime objective of the expedition. The delay would allow us to remain offshore Kerch and resolve the differing interpretations. In consultation, the three of us created a set of waypoints that Kazimierus delivered to our captain as the plan for two days of exploration using the CHIRP, a tool that amazed the Russians who had never seen such detail beneath the seafloor. In the course of our following zigs and zags, the CHIRP lay bare the heads of two previously unknown submarine canyons, the wave-cut terrace of an ancient shoreline with its beach berm and lastly the river delta with its gas-charged sediment derived from decayed swamps, all buried beneath the same uniform sediment cover.

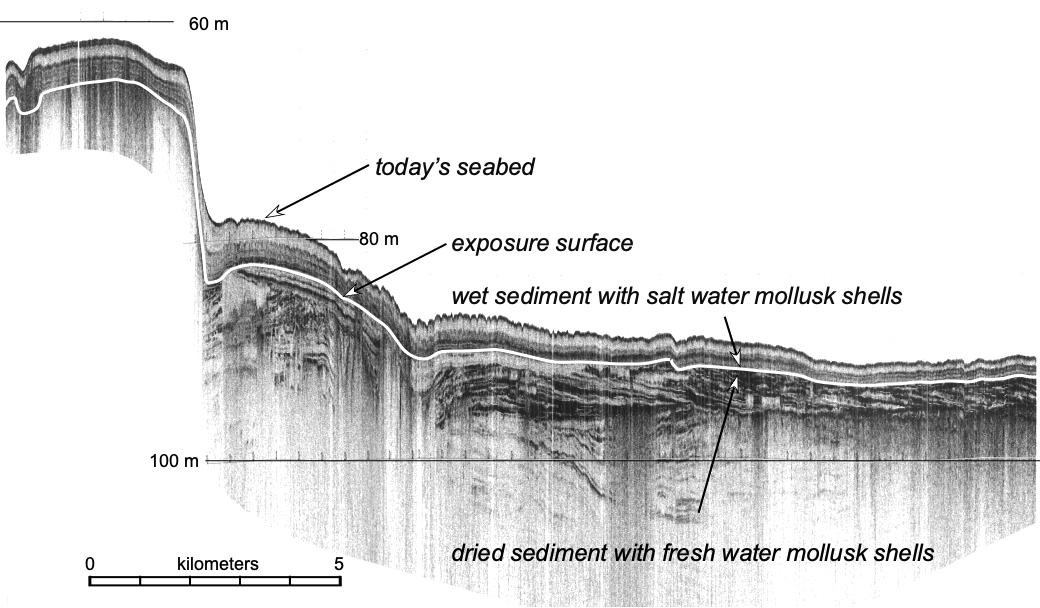

As the CHIRP imagery accumulated and in advance of any direct sampling of the seabed, Walter became more and more assured that the only explanation for the erosion surface was exposure of a former landscape to washing by rain and wind. He conjectured that the uniform drape of sediment had rained down after an extremely rapid submersion by water inrushing from the Mediterranean and drowning the landscape. Candace Major and I marveled at his quick insight, but thought that we should wait for sampling before any conclusions. Kazimierus concurred. Thus, we continued to the Ukraine margin with plans to sample here on our return to home port.

However, once the surveying with the CHIRP began on the Ukraine shelf, the same features reappeared: a buried erosion surface, the uniform drape, and ancient riverbeds. In addition, its buried shoreline was rimmed by coastal dunes. We criss-crossed river channels for 60 miles from the edge of the shelf at 90 meters water depth to the inner shelf at 40 meters depth. When sampling began with 4-meter long gravity core tube with a one-ton weight, only the uniform sediment cover was recovered with only hints of sand and gravel in the core catcher. Apparently, the core tube had stopped abruptly as it hit the erosion surface that Walter had foretold would be a hard ground of dried out mud and sand.

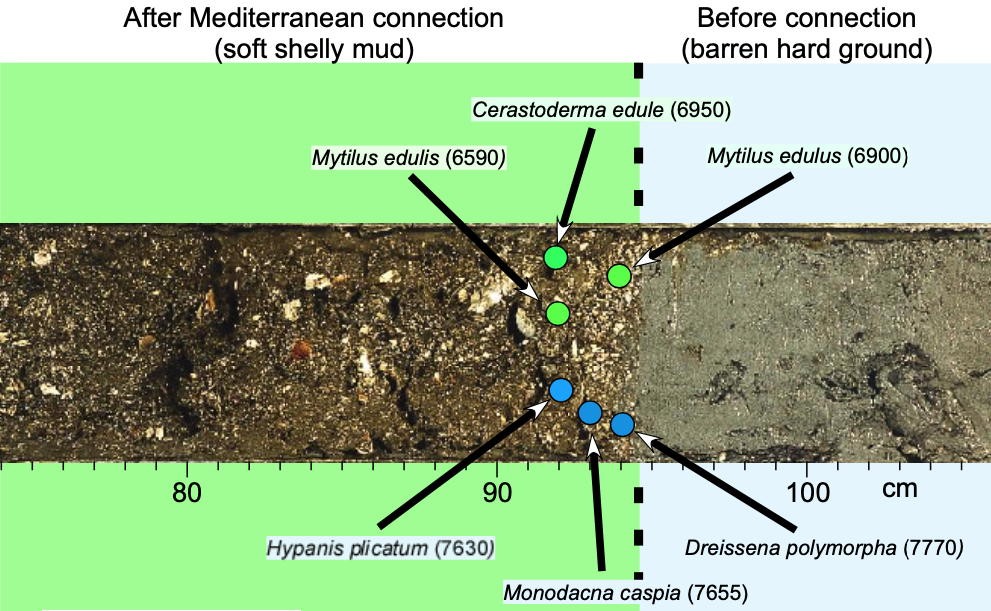

Walter persuaded Kazimierus to instruct the winch operator to pay out the wire attached to the core tube at the highest safe speed possible, approaching freefall. This gamble paid off. The hardground did indeed turn out to be sub-baked mud, so stiff it took great difficulty and strength to cut when the cylindrical core was split lengthwise. Kazimierus had brought instrumentation to measure the content of porewater: less then 10% in the hardground and more than 60% in the overlying uniform cover. The contact between the two formations was razor sharp. Candace found the casts of plant roots and fragments of wood in the hardground. The cover contained perfectly preserved shells of salt water mollusks, including mussels, gastropods and clams. We picked these out with tweezers for later analyses back at Lamont and filled dozens of vials with the shells.

Once the hardground could be sampled in the core barrel, Walter suggested that we take a sequence of cores at decreasing water depths, starting at the shell edge and proceeding landward until time ran out. He hypothesized that if the submergence of the shelf had been nearly instantaneous, the initial mollusks to inhabit the new seabed should all be of the same age as the rapid drowning. If the ages became progressively younger at more shallow locations, the flood would have been gradual and perhaps extended over thousands of years, according to the global sea level history obtained by the radiocarbon dating of corals offshore of Barbados by our Lamont colleague, Rick Fairbanks.

Indeed, when the radiocarbon dates came back from the National Ocean Sciences Accelerator Mass Spectrometry facility at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, our samples from the base of Walter’s drape were exactly the same age, plus or minus 50 years, regardless of the water depth. Walter was ecstatic when he heard the news in a late evening phone call. He had never had any doubts. But the age was younger than he had expected. As he digested the phone call, he became even more excited. He had immediately recalled his reading in journal publications that placed our new radiocarbon age at almost precisely at the time of the first appearance of farmers in Europe. I can remember him saying, “Of course, they were escaping from the flood.” A Walter Pitman flash of deduction, like so many that bore fruit throughout his career. Fifteen years later, when comparing mitochondrial DNA from late European hunter-gatherer skeletons with those of early farmers, Joachim Burger would write in the journal Science that “ancient DNA says Europe’s first farmers came not only from afar, but arrived 7,500 years ago and suddenly spreading in a few centuries from the Balkans to France. It was a major migration event that I never would have believed before.” Barbara Bramanti would write in the same issue, “The farmers were not the descendants of the local population but immigrated into central Europe at the onset of the “Neolithic.” Their date of 7,500 years ago for the onset of the human migration was within 200 years of the age of the first saltwater mollusks that had colonized the drowned shelf of the Black Sea.

With our radiocarbon dates from NOSAMS and isotopic analyses by Candace Major we wrote up our results and submitted a manuscript to Nature in 1996. Walter insisted that we include his hypothesis of a link between the drowning event and the migration of farmers. Our Lamont colleague, Roger Jellinek, heard of our discovery in conversations in the Lamont cafeteria and was intrigued by Walter’s supposition. Roger asked if he could contact BBC and explore interest in a documentary. Their Horizon popular science series answered back with enthusiasm. Walter was immediately onboard. I was hesitant, but concurred. I was worried that if Nature heard about documentary, even if only in the process of production, they would decline publication. The reviews from Nature came back. Acceptance, but with removal of the final paragraph about the lest substantiated human response, which was of the most interest to BBC. The Nature editor had been unconvinced when we wrote in our submission letter: “we have sent our draft manuscript to a number of UK scholars in archaeology (David Harris, Andrew Sherratt, Ian Hodder, Colin Renfrew) and have then met with them in 1995 and 1996 to discuss its ramifications. They all strongly encouraged us to submit to Nature and each seemed willing to be considered as a potential referee.”

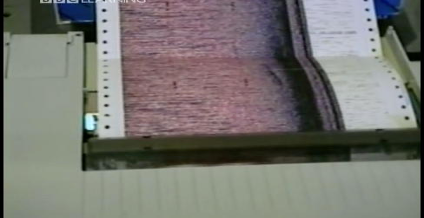

Filming began in New York with a stroll on Riverside Drive, followed by discussions over maps and CHIRP profiles in the Oceanography Building on the Lamont Campus, a mandatory visit with the cameras to the Lamont Core RepositoryThe we were off to Turkey and the Bosporus Strait, through which Mediterranean saltwater had poured into the Black Sea’s freshwater lake, according to our evidence.

A highlight of the adventure was an outing in the Bosporus Strait where I climbed into a fisherman’s small boat. The Epic of Gilgamesh (the earliest account of a huge mythical flood) had referred to a crossing of the “Sea of Death” using “stone things” and “snake-like vines”. It had been well-known in antiquity that there were two currents in the strait travelling in opposite directions. The fresher outflow from the Black Sea flowed south on the surface. The salter Mediterranean water poured north over the bottom current and sank into the interior of the Black Sea. Perhaps Jason and the Argonauts had used this knowledge in search of the Golden Fleece.

The fisherman brought a large woven basket into which he had placed about 75 lbs of stones. He and I lowered the basket into the water while we slowly drifted south in the upper current. But once the basket got to a depth of about 50 meters (~150 feet) our small boat took off in the opposite direction and towards the Black Sea at a clip of 3 to 4 knots. Walter and the film crew were astonished. I was surprised by Walter’s astonishment. It was unlike Walter to have a moment of doubt in the power of myths.

Another insight into his quick mind and spontaneous humor came when filming Niagara Falls. In his dressed slicker and gazing at the majestic cascade through a cloud of mist, he declared on camera that “the Bosporus cataract had been 50 times larger.” Startled and breaking filming tradition, the director inserted himself into the shot and asked on camera “How did he know?” Walter replied, “How do I know? Why I calculated it!” Vintage Walter Pitman.

Then came a setback. Despite our insistence that the Nature article be published prior to release of the film, BBC announced an earlier release date. Nature responded by pulling our article that had already been typeset. Fortunately, a reviewer saved the day by offering to published our manuscript in another journal of which he was the chief editor. But it was a disappointment to Walter in particular not to have gotten a broader exposure from Nature.

The alternative publication, necessarily condensed for the format of Nature, lacked much of the supporting material such as the CHIRP profiles and core photographs. However Walter’s did get his “human impact hypothesis” published in a Romanian journal where it was widely available to eastern European archaeologists excavating Europe’s first farmers.

Next came our book, “Noah’s Flood, The New Scientific Discoveries About the Event That Changed History”, published in 1998 by Simon & Schuster. It was a Herculean task in which we were assisted by many, including Walter’s daughter, Amanda. Walter’s legendary story telling is expressed in his chapter “On a Golden Pond” in which he ventures from oceanography to human evolution commencing with Modern Man’s introduction to Europe, the Ice Ages, post-glacial melting, the diaspora from the Black Sea and the way the Black Sea’s flood is voiced in the myths sung by ancient bards.

Walter’s story telling continued with his move to the Hebrew Home in Riverdale. He entertained and humored his visitors with tales beginning as a youth during ventures in boats with his grandfather, his first voyage on the Vema, and his famed discovery of symmetry in the renowned Eltanin 19 magnetic profile. He cherished his days at Lamont as if they were a gift. I miss him dearly.