A Tribute to Walter Pitman: His Science and Long Friendship

Lynn R. Sykes

Higgins Professor Emeritus of Earth and Environmental Sciences

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades New York 10964

My scientific life changed abruptly on a single day in the spring of 1966 when James Heirtzler called Jack Oliver, the head of the seismology group at Lamont, to say that he and graduate student Walter Pitman had some exciting new evidence about the Earth’s magnetic field in the Southeast Pacific. Pitman and Heirtzler proceeded to show us what became known as the "magic profile" of magnetic anomalies across the Pacific-Antarctic Ridge in the remote southeast Pacific. They showed us that magnetic anomalies on either side of that branch of the Mid-Oceanic Ridge System were symmetrical even at the smallest detail out to 300 miles (500 km) from the center of that ridge. To demonstrate this, they made a reverse acetate image and overlaid it on the original. They matched almost exactly, wiggle for wiggle. Cooling seafloor was acting like a giant tape recorder as the earth’s magnetic field reversed direction about every half a million years. Their profile shows greater symmetry than any of the other profiles published during the last 54 years.

How did Walter make this outstanding contribution to what became known as plate tectonics? One was being open minded. He was mature after working in industry before enrolling as a graduate student at Lamont. He spent many months at sea, especially in the far southern Pacific the site of the “magic profile” and one of violent weather and ice bergs. He was part of a graduate seminar in paleomagnetism, one of the few areas of the earth sciences that took seriously continental drift and earth mobility on a grand scale. He became familiar with the work of Vine and Matthews, who proposed in 1963 that new oceanic crust formed at mid-ocean ridges received a magnetic imprinting as the Earth’s magnetic field reversed. He found clear reversals in records collected by the ship Eltanin in the far and remote southeast Pacific.

After a long night of work, Walter pinned his “magic profile” to Neil Opdyke’s door at Lamont and went home to bed. Neil, who received his PhD in paleomagnetism and paleoclimate in the UK, was one of only two scientists at Lamont who took continental drift seriously. Realizing the importance of the “magic profile” the next morning, Opdyke phoned Pitman and said get your behind in here immediately. The rest was a milestone in the earth sciences when the Pitman-Heirtzler paper was published in Science in 1966.

In 2000 I described briefly what happened to Walter when his paper with Heirtzler was published in 1966. He called his mother to tell her that the New York Times reported their work in a major story. He asked her, “Does my father know about it?” She said, “Yes indeed; he went down to buy all of the copies available at our local newspaper store.“ Walter’s father expected him to be a businessman. He then became “my son the oceanographer.”

Walter went on to work with many marine scientists and graduate students at Lamont on magnetic anomalies, seafloor spreading and movements of the continents during the last 80 million years. He interacted exceedingly well and fairly with students and professional scientists. Everyone adored him. He was always a gentle person who rarely showed anger. He loved working with Columbia students and considered them to be very bright. Several years before his death, he travelled with his walker and some pain to meet with students on the main campus of Columbia.

About two years after I arrived at Lamont as a grad student, I bought a tiny used Fiat 500 in the far reaches of Brooklyn for $100. On my way home, it broke down on the West Side highway not far from where Pitman and I lived. Walter drove by, saw my plight and pushed me to a garage. We became fast friends and scientific colleagues for the next 58 years.

As soon as I saw Pitman’s “magic profile” I knew I had to work immediately on the new transform fault hypothesis. I started the next morning on mechanisms of earthquakes from oceanic fracture zones and ridges. This was one of the few instances in my scientific life when I immediately stopped working on everything else to concentrate on testing the transform fault, seafloor spreading and continental drift hypotheses.

While I was in Fiji in 1965 working on deep earthquakes, James Dorman of Lamont wrote to me about a paper published that July by J. Tuzo Wilson of Toronto University. He described a new class of faults that he called transform faults. It involved two concepts that had many doubters: seafloor spreading and continental drift. An idea began to germinate in my mind that I could prove or disprove his hypothesis by using focal mechanisms of well-located earthquakes. My seeing the magic profile in 1966 led me to stop germinating and immediately to start using seismological data from earthquakes along mid-oceanic ridges and what were then called fracture zones to test Wilson’s proposal. Fracture zones are now called transform faults.

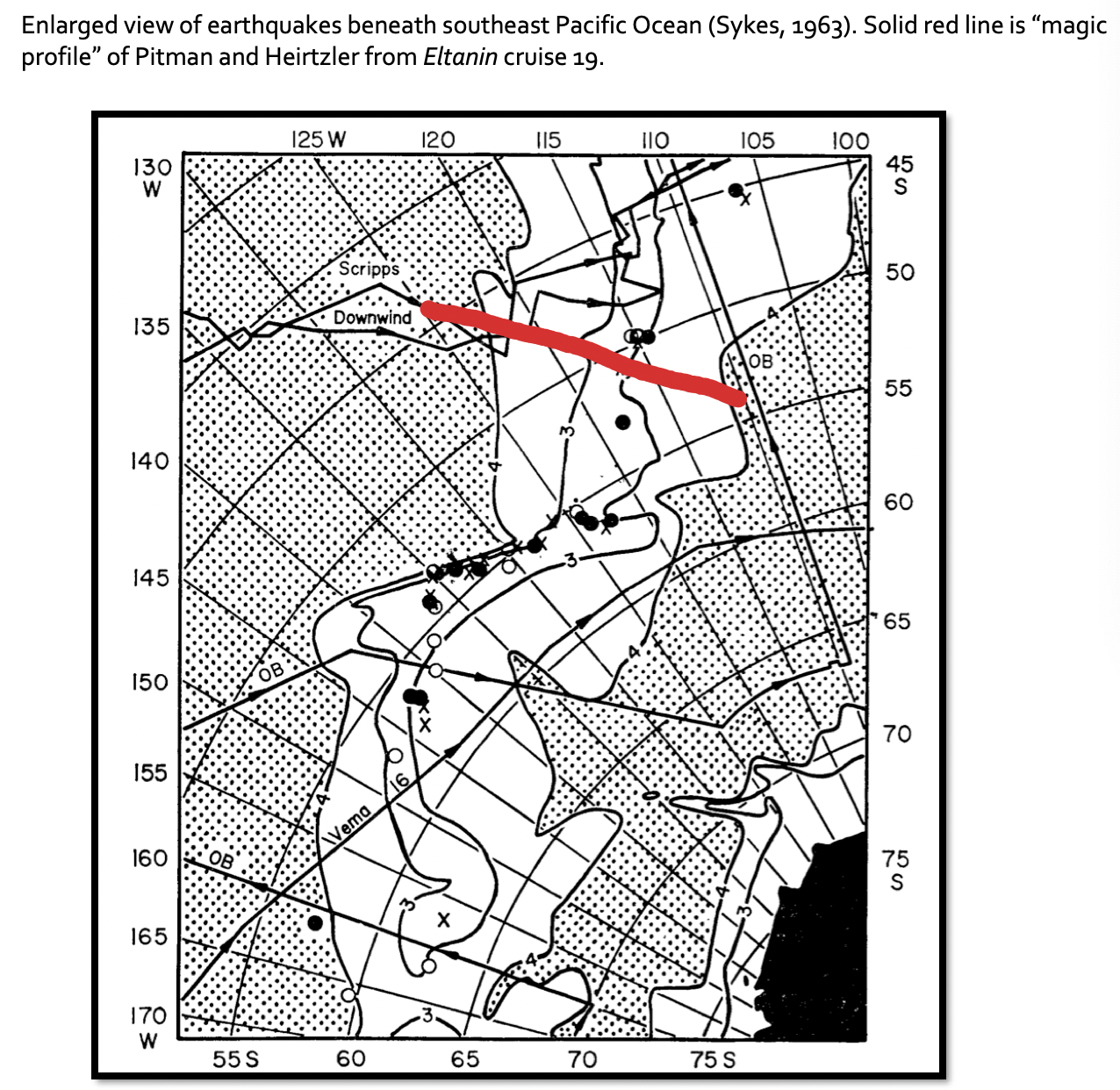

Prior to 1966, fracture zones were described as enigmatic long, linear zones of rough topography on the sea floor, some of which intersected mid-oceanic ridges. My work on fracture zones came about indirectly through my examination of surface waves generated by earthquakes along the Pacific-Antarctic Ridge. On plotting revised computer re-locations, I found that they were confined to narrow bands along parts of the world- encircling mid-oceanic ridge system (see figure below).

What particularly caught my eye was the concentration of earthquakes near latitude 55o S. The northeasterly trend of earthquakes along the ridge to the south suddenly changed direction to easterly at 55o S, 135o W. It then resumed a northeasterly course at 56o S, 122o W. I proposed that a major fracture zone nearly 620 miles (1000 km) long trended nearly east-west and intersected the ridge system at 55oS. It was seismically active only between the two ridge crests but not farther east or west. How could a great fault or fracture zone suddenly end? The zig-zag pattern of shocks and the lack of them beyond those ridge segments was one of Wilson’s key pieces of evidence for his proposal in 1965 for what he called transform faults.

When I showed my pattern of earthquakes along the Pacific-Antarctic Ridge in 1962 to Maurice Ewing, the Director of Lamont, he arranged for the ship Eltanin to map the great fracture zone at 55oS. Its fierce weather and sea conditions required a ship to have a strong, re-enforced hull. Pitman sailed on the Eltanin to map the region. He was drawn to variations in the Earth’s magnetic field somewhat farther to the north (red line in figure) along what was soon called his “magic profile.” Fortunately, that area was simpler in terms of spreading and magnetic anomalies than the fracture zone just to its south.